We Killed Wonder

Modern Rationalism, Scientific Pretension, and the Loss of Desire for God

“The world will never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder.”

— G.K. Chesterton

“Listen to this, O Job; stand still and consider the wondrous works of God”

(Job 37:14).

Modern people like to think of themselves as disenchanted because they are educated, sophisticated, and sensible. Our generation has almost entirely outgrown the wonder of the supernatural. We have replaced mystery with explanation, awe with excessive analysis, reverence with reason. Boredom, we tell ourselves, is simply the cost of progress.

That story flatters us. It also lies.

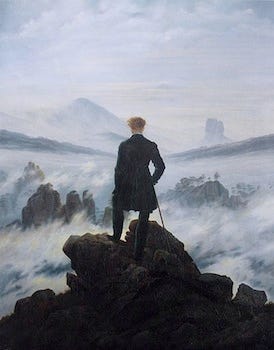

The modern world does not suffer from a shortage of wonder. It suffers from a cultivated resistance to it. Mystery has not been removed from reality. It has been rendered unnecessary. This decisive shift is not in the world, but in the human posture toward it.

Our tragedy is that we have chosen boredom as the path of least resistance.

The Pretence of Total Explanation

Contemporary scientific culture often trades on a quiet but corrosive assumption. It is not merely that science explains many things really well. It is the insinuation that, in principle, science can explain everything that matters.

This assumption is not science at all, it is “scientism.”

When figures like Richard Dawkins insist that the universe is ultimately indifferent, or when Steven Pinker argues that scientific progress has rendered older religious explanations obsolete, the claim being made is not only intellectual, it is moral. We are being trained to expect a world that makes no demands beyond what we choose to acknowledge.

Yet the irony is blatant and obvious. Even at the furthest edges of contemporary physics, explanation increasingly consists of abstraction, symbolic modelling, and classification. We name forces we could never visualise. We describe realities we cannot intuit. We generate equations that predict behaviour without conferring meaning.

This is not the disenchantment promised. It is mystery with better notation.

What has changed is not the depth of reality, but our patience for it.

Rationalism as a Formation of Desire

The real enemy of wonder is not knowledge, but rationalism. Rationalism is not disciplined reasoning. It is the belief that reality must submit to human mastery in order to be meaningful. The genius of this lie is its subtlety. To explain is to feel powerful. To master the unknown is to feel safe. But rationalism does not master reality. It diminishes it until it fits our grasp.

This belief does not merely shape arguments. It forms people.

Wonder requires humility and receptivity. It demands that we allow reality to address us rather than placing ourselves permanently over it. It presupposes modesty, attention, and the acceptance of limits.

Rationalism trains us otherwise. It produces subjects who demand immediate explanation, grow irritated by mystery, and interpret astonishment as intellectual failure. Over time, such people do not lose access to wonder, they lose the appetite for it.

The result is self-induced boredom.

Boredom as Spiritual Verdict

Boredom is one of the most revealing features of modern psychological life. We are endlessly stimulated and chronically restless. Surrounded by information, we complain of meaninglessness. We chase novelty and tire of it almost immediately.

This is not a minor emotional inconvenience. It is a spiritual indictment.

Boredom arises when a world stripped of transcendence can no longer sustain the weight of human desire. A closed world cannot satisfy creatures made for more than closure.

We have explained the world in such a way that it no longer addresses us, and then we are surprised when it fails to hold our attention. We have trained ourselves to inhabit a reality that makes no claims, and we experience that absence as emptiness.

Boredom exposes the lie at the heart of modern disenchantment. It reveals that the problem is not too much mystery, but too little willingness to receive it.

Disenchantment Is Chosen, Not Forced

Sociologist Max Weber famously described modernity as “disenchanted.” What is often forgotten is that Weber did not celebrate this condition. He saw it as spiritual bankruptcy.

Philosopher Charles Taylor later clarified why disenchantment persists and poisons. Modern people live within what he calls an immanent frame, a way of imagining the world as self-contained and closed to transcendence. God is not denied, but bracketed, tame, and optional.

Within this frame, the modern self is buffered. Meaning no longer presses in. Reality waits politely for our interpretation.

This is why disenchantment is not imposed upon us. It is preferred. A disenchanted world is easier to manage. It does not interrupt us. It does not summon gratitude or obedience. It does not threaten autonomy.

Wonder, by contrast, is disruptive. It implies that we are not sovereign, that reality precedes us, and that meaning is given rather than generated.

We have not been robbed of wonder. We have learned to insulate ourselves against it.

Scripture and the Posture of Wonder

Scripture presents wonder not as an emotional high, but as a posture of attention.

Consider Moses at the burning bush. He does not rush to analyse what he sees. He turns aside. That decision matters. The bush burns without being consumed, but it is Moses’ willingness to attend that opens the encounter. God does not explain himself. He reveals himself.

The ground becomes holy not because Moses comprehendsit, but because God addresses him. Wonder here is not spectacle. It is interruption. It arrests Moses’ productivity and reorients his vocation.

The wilderness generation provides the counterpoint. They are not deprived of marvels. They are bored by them. Manna becomes monotonous. Gift becomes grievance. Familiarity erodes gratitude. Boredom hardens into complaint.

Scripture treats boredom not as exhaustion, but as ingratitude. It is the refusal to receive what is given because it no longer astonishes.

Wonder as a Human Capacity

Wonder is not a fleeting emotion or a response to novelty. Animals startle. Humans wonder.

Wonder is a uniquely human capacity to apprehend reality as meaningful beyond immediate utility. It arises when finite reason encounters a world that is intelligible yet inexhaustible. It presupposes rationality and acknowledges finitude.

Classical Christian theology has always recognised this. Augustine warned that familiarity dulls wonder not because creation becomes less marvellous, but because the heart grows inattentive. Aquinas identified wonder as the beginning of wisdom, not its enemy.

Wonder is not ignorance awaiting explanation. It is perception rightly ordered.

Christ and the Redemption of Wonder

Christian faith does not resolve wonder by explanation. It fulfils wonder by revelation.

The incarnation does not dazzle. It bores the impatient. Nazareth produces no spectacle. The infinite enters the ordinary without display. This is not a failure of communication. It is a refusal of manipulation.

God does not satisfy the modern demand for astonishment. He offers instead a wonder that can only be received through attention, patience, and faith.

The Word becomes flesh. The Creator becomes creature. Mystery is not solved. It is deepened and localised. God becomes near enough to be ignored.

Here boredom reveals its true object. The incarnation offends not reason, but impatience. It refuses novelty and insists on presence.

Reformed theology insists that grace restores nature rather than destroying it. The same is true of wonder. Redemption does not suppress astonishment. It reorders it toward its proper end, worship.

The Church and the Temptation of Spectacle

A church that loses wonder will attempt to replace it with spectacle. When attention is thin, stimulation becomes necessary. When boredom reigns, volume and novelty are mistaken for transcendence.

But spectacle cannot cure boredom. It can only postpone it.

The recovery of wonder will not come through technique, atmosphere, or performance. It will come through a retraining of attention. Through learning again to receive reality as gift rather than resource. Through resisting the demand that God justify himself by entertaining us.

This work is slow. It is liturgical rather than technological. It forms patience rather than excitement.

Conclusion: Choosing Wonder Again

Modern scientific philosophies have not explained the world. They have explained it away, not by answering its mysteries, but by teaching us to stop asking why they matter.

The result is boredom, restlessness, and a dissatisfaction no amount of information can heal.

Wonder has not vanished. It remains God’s gift to humanity, the capacity to encounter reality as address rather than object, as gift rather than raw material.

Recovering wonder will require repentance. A turning from mastery to reception. From control to gratitude. From boredom to worship.

The world has not grown small. We have. And only by learning again to wonder can we recover the fullness of our humanity before God.